updated 11/12/08

|

Canoe from the

Gilbert Islands (Kiribati), Micronesia

|

|

click on pictures for larger images

Historical Notes

The picture Europe has (had) of the Southern Seas

is still very much

the product of the great voyages of the discoverers of

the 18th Century: Wallis, Cook, Bougainville, to name just a few of

more the

important commanders. Experiences made and impressions gained by

various travellers found their way into the World literature, think of

Melville, Stevenson or Chamisso. Fine art, particularly the paintings

by Gaugin, also shaped our mental picture. The liberal social customs

of the (female) islanders fired the imagination of the male European

population - who doesn't know the story of the mutiny on HMS Bounty !

The interest in and the scientific instrument to

investigate foreign cultures slowly developed over the past 200 years.

So much of the material and spiritual culture of Oceania disappeared or

was replaced (often deliberately) by European goods and concepts before

it could be documented. A process that accelerated since the early

decades of the 19th century due to increasingly frequent contacts with

European and US whalers, traders and missionars. This affected also the

perhaps most important cultural and technological achievement of

Oceania, namely the sea-going boat and the navigational traditions

without which the settlement of the Pacific Islands would not have been

possible.

Based on the geographical situation and the

ethnographic results of a complex history of settlement (e.g.

IRWIN, 1994) today we

distinguish the three

mega-regions of Melanesia (i.e. the islands of the dark-skinned

people), Polynesia (i.e. the region of the numerous islands), and

Micronesia (i.e. the region of the small islands). The cultures of

Poly-

and Micronesia are particularly characterised by the absence of metals

and pottery, which is due to lack of suitable raw materials. In

pre-European times all artefacts were made without the use of metals.

Considering the type and limited availability of raw materials the boat

building techniques were at an amazingly high level of development. In

many regions sophisticated techniques for assembling big boats, or

rather small ships, from small planks had been developed. However, such

boat largely had ceased to be built before the first Europeans had the

opportunity to view them. Nevertheless the first travellers were

suitably impressed by their size and numbers. Today, traditional boat

building is only practised in a few remote regions that do not have the

resources to acquire the products of Western technology.

These important cultural achievements, as

consequence, have almost completely disappeared from the daily life and

relegated to museums (e.g. the Bernice

P. Bishop Museum on Hawaii). The

Ethnographical Museum

in Berlin is lucky enough to have collection of

several of the most important boats from Oceania. Most have been

collected during the early years of the 19th century, when parts of

Micronesia and Melanesia were colonies of the German Empire. Others

have been built to order for the museum after WWII or collected during

the expeditions of its then director Gerhard Koch. Next to original

specimens

and models in other museums (in Europe e.g. those in Hamburg, Bremen,

Paris, London) provide the field research and compilations by HADDON and HORNELL

(1936-38)

and NEYRET

(1976) the most

important source for

the prospective modeller. In addition there is a great number of

monographs and journal articles concerned with the material culture of

the various archipelagos, including their boat building traditions. An

overview over this literature provides e.g. the bibliography by GOETZFRIDT

(1992).

The Prototype

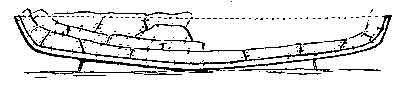

The sail-powered outrigger boat (Fig. 1)

from the Gilbert

Islands (Fig. 2) attracted my

attention already during my very first

visit to the museum in Berlin in 1973. With permission by the museum I

have been able to photograph the boat with all its details and to make

sketches and measurements in preparation for the model (Fig. 5) in 1995. The

most important scientific study on these boats is that of GRIMBLE (1924), whose observations

have been largely

confirmed by DREWS (1945).

According to the

field research by

KOCH (1961, 1984) in the 1950s the

techniques did not fundamentally change, but the construction of the

museum boat, which was built in 1951 and transferred to the museum in

1964, was somewhat simplified in comparison to the sources quoted.

The culture and, hence, the boat building

tradition was largely determined by the scarce resources of the low

coral islands of the Gilbert archipelago (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the

indigenous

pandanus, coco nut and mangrove provided suitable raw materials for

boats, though really suitable timber is extremely scarce. To become

boat owner required the acquisition of a suitable supply of timber

first. In spite of those limitations the Gilbert islanders managed to

develop the fastest sail-powered boats of World that are not based on

modern science and engineering technology. Given the right wind and sea

conditions on the inner lagoons of the atolls, these boat reach a speed

of 20 knots.

The boats from the Gilbert Is. (Fig. 4) differ

from most of the other boats of similar size in Oceania in that

they are not real dugouts or 'extended' dugouts, but are constructed

from planks on a keel (Fig. 6);

though the keel could be possibly

interpreted as a rudimentary dugout (c.f. GREENHILL

,

1976). This rather sophisticated technique probably was developed by

necessity, as no real trees were available on these poor islands. In

the old days the planks were shaped from the timber using axes and

adzes. The latter traditionally having blades made from the Tridacna spec. mussel. In historic times

tools made from imported steel or even imported tools were used. Given

the rather knotty and crooked trees the rule was: one tree trunk = one

plank. Since ready cut planks became available from European and

particularly North American sources these were preferred and the sides

of the boats built up from continuous strakes. It was interesting to

observe that the old techniques were revived when timber imports

stalled during WWII.

|

|

|

|

|

|

(6) Planking diagram

|

(7) Keel piece set up

|

(8) Cross section

|

(9) Rabetted stem piece

|

(10) Spacer sticks

|

| (GRIMBLE,

1924) |

The following paraphrases the prototype

building description by GRIMBLE

(1924). After various preparations of logistic and spiritual nature the

building proper began by propping up the three-sided keel (Fig. 7) that

receives a groove along its central line to act as a bilge (Fig. 8).

Ideally the keel is made up from one piece. Trestles and pegs coerce

the timber into the desired shape, that is a slight hog. In addition,

it is made slightly concave, opening towards to the outrigger, the

objective of which is to counteract the drag caused by the outrigger.

The stems (the boat is symmetrical) also have a triangular

cross-section an receive a shallow rabbet (Fig. 9). The actual shape of

the stem pieces are determined by the available timber, but the builder

tries to achieve a symmetrical appearance. Keel and stem pieces are

butted together only. The fit is tested using a touching-up paste made

from soot. The pieces are lashed together using twine made from coconut

fibre. The passage of the cord is recessed to limit chafing when the

boat is hauled ashore etc.

The hull is built up by the shell-first method. The

main cross-section

is slightly asymmetric (Fig. 8),

as with most outrigger boats, in order

to counterbalance the turning moment of the outrigger. The side facing

away from the outrigger is almost flat and vertical. This asymmetry is

obtained by a simple former that spreads out the keel-planks (Fig. 10). The strakes

run parallel to the keel (Fig. 6).

Their individual pieces are carefully fitted

to each other using the touching-up paste. The planks are lashed

together along their edges using twine made from coconut fibre and

caulked with pandanus leaves that had been chewed(!) through and oiled.

The hull is coerced into its final shape using thin branches as

spacers. Once the master boatbuilder is satisfied with the shape,

half-frames are fashioned from suitable pieces of wood and tied down

with

twine (Fig. 8). All cord

running on the outside of the hull are recessed.

The frames reach somewhat above the topmost planks (Fig. 8) in order to

provide a fixing point for two pairs of stringers that run in- and

outboard along the sides of the hulls and fashioned from rather

straight thin branches.

A further stiffening of the shell is provided by the various

members of

the outrigger that run across the wales (Fig. 11). The main beams are

recessed into the 'wale' (Fig. 8).

Whenever members of the outrigger cross each

other or suitable parts of the hull, they are tied together using

coconut twine. The main beams also serve as seats when paddling and

steering. The outrigger parts are constructed from well-seasoned pieces

of the coconut palm tree (Fig. 13).

As the native wood has a too high density to

be useful as float, the islanders have to rely on flotsam. Suitable

pieces are treasured to the day they are needed for this purpose. Each

archipelago and each island has its own technique for joining the float

with the outrigger. Here short, Y-shaped pieces are lashed on top of

the float first (Fig. 14). The

main beams are then lashed to these

pieces (Fig. 15).

After completion,

hull is

sanded down using shark or ray skin and receives protective coatings of

oil and a lime wash.

The triangular sail originally was woven

from strips of pandanus

leaves (Fig. 16). The process

of bleaching, beating soft and weaving is very

labour-intensive and sails cut from imported canvas had replaced the

traditional ones for decades. Canvas, however, has the disadvantage of

drying more slowly after the boat should have happend to be ditched

than sails made

from oiled pandanus leaves. Today, sails made from synthetic fibres are

preferred. The sail is bent to a 'yard' and a 'boom' using short

pieces of twine (Fig. 16). A

rather massive piece of wood with several

depressions serves as mast spur. These depressions allow for varying

trims of the rig. The 'standing' rig consists of two stays and a branch

with a crotch at its end that supports the mast on its windward side (Fig. 12 and 13).

There are also a couple of shrouds fastened to the outrigger. The yard

is hoisted by a halliard running through a hole in the mast. The sheet

is not directly bent to the boom, but to a primitive block running

along a bridle, but not actually forming a purchase. The shrouds may be

rigged in a similar fashion. Perhaps this is an imitation of European

rigging practice. The yard is either made from a long branch ending in

a crotch, or has a short piece with a crotch tied to it. This crotch

rests on the forward-facing of the two short cross-pieces that are

provided at each end of the boat (Fig.

17).

When going through the wind the sail is shifted around and the

crotch rested in the cross piece on the other bow. The boat is always

sailed with the outrigger wind-wards. It is steered with a paddle

fashioned from a single piece

of wood. The paddle is tied to a special rest on the respective stern

of the boat. Conversely, the paddles used for propulsion are built up

from two pieces of wood. The boat's equipment is completed by a bailer

and a pierced big chunk of coral serving as anchor.

The Model

The model was

constructed in 1:87 or HO-scale, mainly because the

German company PREISSER produces figurines that can be used to create

the 'islanders'. The hull of the model was shaped from Westindian

boxwood (Costelo). Costelo is

rather similar to the European or Asian boxwood in grain, texture and

workability, but rather cheaper. On the PROXXON table saw a billet of 6

by 7 mm cross-section and of 95 mm length was cut from the stock. The

further shaping was carried out very much like you would do on a solid

hull model, but on a rather small scale. Side elevation and 'deck' plan

were constructed on the computer from the available drawings. This has

a number of advantages: the endless reproducibility also at different

scales; mirror images of parts can be produced without loss in quality;

etc. The billet was marked with an inscribed centre line for reference

and printouts of elevations deck plan stuck on with just a bit of PVA

glue. The shape of the hull was then roughened out on the table saw

first. For the next step the stationary drilling machine was converted

something like a drum sander by mounting one of those expanding

mandrels for emery paper tubes. The hull billet was passed along the

drum free-handedly to round off the plan view. Both ends were cut off

according to the rakes of the stem pieces. A couple of paper templates

serve as guides for sanding the billet to the desired unsymmetrical

V-shape. The hull surface is smoothed down with emery paper of

increasing fineness. The hull is now ready for hollowing out.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(18)

|

(19)

|

(20)

|

(21)

|

(22)

|

(23)

|

| Scenic Display |

The

hollowing out is done with various round and flame-shaped

milling cutters mounted in the mini-drill. The remaining thickness is

easily controlled by holding the hull against a light source. Ideally

it should shine through uniformly over the whole hull. Of course the

area of the keel is left thicker. Prototype hulls are only 2 or 3 cm

thick, which translates into about 0.3 mm at the chosen scale ! The

inside of the hull is carefully smoothed using rotary diamond tools and

rubber-bound grinding wheels (CRATEX®-wheels).

On the outside the planks seems are lightly incised using a

knife-shaped engraving tool. These lines are later picked out in dark

ink. The recessed ties between the planks are also marked using the

engraving tool (Fig. 7). The wood was lightly stained with a dark grey

wood stain. Costelo does not take stain very well, which was actually

of advantage here as a slightly weathered appearance was intended. The

surface was sealed using wood primer (Schnellschleifgrundierung G1 from

Clouth, Germany) and lightly rubbed down using no. 000 steel wool.

The float was fashioned from a short stick of

beechwood, its rougher

appearance than boxwood being more akin to the prototype wood. The tree

'branches' that make up the outrigger and strengthening pieces of the

hull are made from copper and brass wire of different thickness. To

this end pieces of appropriate length were rather abused by bending,

straightening, hammering and covering coarsely in electronic soldering

tin - until they looked somewhat like branches. Were needed also

crotches were soldered on. These wire branches then received a base

coat of HUMBROL British Army Desert Yellow that comes

close in hue to the woods used.

All parts of the outrigger were tied together prototype

fashion ! The

material used for this is very fine two-ply twisted polyester thread as

once used for stitching up ladies' tights. Since mending tights seems

to have gone out of fashion, new supplies of this thread seem to be

impossible to come by. If you are lucky it may turn up on flea markets

(sellers always seem to raise an eyebrow when a man buys such stuff

...). The thread is dyed using mahagony wood stain, which gives it the

colour of coconut twine. Several length of this material are prepared

and the ends stiffened with a drop of zapon lacquer (also from Clouth

in

Germany) to facilitate threading. I prefer this lacquer over

cyanoacrylate glue because it is easier to apply controlled (with a

toothpick or an old paintbrush), does not degrade to this whitish

powder - and can be re-dissolved in an emergency. The bindings are done

as per prototype, for which sketches were available from the published

literature and my own observations. Some compromises had to be made, as

the thread is extremely fine though, but still some five times

overscale. Therefore only two rounds were taken at each binding as

opposed to several in the prototype. The knots were secured with a fine

drop of lacquer.

The whole boat was given a thin coat with light-brown

furniture varnish

(CLOU®

Möbellasurlack), which makes the appearance more uniform and gives

it warm tint. The hull again was lightly rubbed down with steel wool to

give it a silky appearance and to provide a better key for the final

wash in dilute white water colour. This will appear patchy by intention.

The paddles were carved from thin Costelo shavings. The handles were

reduced to the correct diameter (0.5 mm) using a home-made drawing

plate. The bailer (2 mm long!) with its characteristic inside handle

was carved from a scrap piece of Costelo.

The prototype pandanus leave matte sails have a rather

coarse

appearance compared to canvas, but still were of incredible fineness as

is evidenced by museum samples. Starting material for the model sail

was the very fine silk weave that is used for model airplanes. A scaled

copy of the sail plan was stuck to a piece of stiff cardboard that then

was covered with cling-film. Strips of the silk were cut of a width

that is to scale with the width of the individual mattes from which

the sail is composed. This strips were laid out on the sail plan with a

narrow overlap to represent the seams and pinned down outside of the

sail. The whole arrangement was then lightly brushed in the wood-primer

mentioned. This stuff has many good properties including of drying

within a few minutes. Once dried the sail is cut out allowing a margin

for turning over as doubling. The doubling is bent over a thin copper

wire laid into the seam and tacked down using cyanoacrylate glue - the

only place were CA was used. The wire allows to sculpt the sail and

prevents the silk from ripping when bent to the yard and boom. The next

step was painting the sail in acrylic paints, whereby the base coat was

applied by airbrush. The texture of the silk was somewhat highlighted

by 'dry brushing'. As the matte sails have the appearance of polished

wood due to their repeated treatment with coconut oil for

water-proofing was model sails were given a light coat of semi-gloss

acrylic varnish.

The model was finally rigged up using the thread mentioned above and

all knots secured with drops of lacquer.

The Figurines

Human

figures provide the necessary scale and illustrate

the mode of use of such boats. A scenic display illustrates also the

environment in which these boats were built and used.

The

well-known German company PREISSER makes a range of nude figurines,

called 'Adam & Eve', in various scales. Even those at the 1:87

scale are broken down into individual bodies, arms, legs and heads,

allowing the composition of different postures. The tooling is

incredibly detailed, allowing even to distinguish individual finger

joints ! If one can trust Western photographers and their selection of

models, many Polynesian and Micronesion were well-proportioned by

'classical' standards, often athletic, but sometimes with a slight

inclination to obesity. My personal theory on this is that only people

of a robust constitutions with certain reserves of body fat would have

survived the arduous voyages during their migration over Oceania, but I

cannot reference this scientifically. Anyway, the 'academic'

proportions of the PREISSER set makes them very appropriate for those

islanders.

Photographs

in KOCH

(1961) and KENNEDY

(1931) show most people still wearing the traditional Pandanus leave

skirt. It is not certain, of course, whether they did this to just

please the ethnologist or whether their limited cash would not allow

them to buy Western goods. The otherwise ubiquitous printed cotton had

replaced the traditional tree leaves and bark tissues already on

Gaugin's pictures. The scenic display tries to capture some epic time

before Western goods swamped the markets, particularly in the wake of

WWII.

From the supply of body parts I composed three figures.

Two of them

operate the boat, while the third one is of more decorative nature. In

many regions fishing boats were 'tabu' for women, but they operated

boat themselves to cross lagoons or even to travel between islands. The

skirts or aprons are made from no. 000 steel wire and very thin paper.

The body parts were assembled using liquid polystyrene cement, which

was

also used to attach the pieces of clothing. Gaps were filled using HUMBROL

putty, which was painted over with the liquid cement to smooth and

blend-in the joints. The figurines then were given a base coat in a

dark-flesh

artists' acrylic paint using the airbrush. This base coat was left to

set for several days. Shadows and lights were added using appropriately

toned down and diluted acrylic paints. A light touch from the airbrush

in a reddish-brown translucent paint particularly in the shadows adds

depth and unity to the paintwork. The the flesh parts of the figurines

were finally varnished in a mixture of gloss and matte acrylic, while

the fabrics were left matte (Fig. 10).

The Scenic

Display

It is helpful to think of a 'story board' for the

scene first. Thus, I have been thinking of a sunny day with good, but

not too strong breeze blowing across the inner lagoon of one of the

islands. Consequently, there ripples and a bit foam, but no high seas.

The water is only a few metres deep, so it would appear crystal clear

and in a more greenish than deep blue colour. The scenery forms an integral part of the glass

case described in the following section.

While one has to be cautious using clear plastics

for representing the sea, this is case where it is almost a must. By

chance I came across a piece of daylight fluorescent acrylic glass and

thought this would make a nice effect. The fluorescence becomes

only visible at the cut edges. However, the acrylic artist's gel used

to model the ripples and wavelets has a refractive index close to that

of the acrylic glass. Thus some of the fluorescence appears on the

surface of the 'water'. The acrylic glass plate is cut to size to fit

on the base of the glass case. Work continued with milling a suitable

recess for the boat using various mills and diamond tools in the

mini-drill. In the next step the water was modelled. The base of the

case was painted in something like a turquoise colour and, after the

paint had thoroughly dried, the acrylic glass plate was glued on. Then

the boat was set into the recession and stuck into place using acrylic

gel and the water modelled around it. Finally white highlights were set

on the waves, around the boat and the steering paddle using artist's

acrylic paint.

The Display Case

The idea of a glass case with a

slanting front came to me when I saw some jewellery display and I

thought it makes an attractive change to the usual brick shape. As one

views the main pane almost perpendicularly this reduces also

reflections. Also, this semi-pyramid shape is rather appropriate to a

sailing boat.

Since having read McNarry's book on Miniature Shipbuilding

I have

constructed my glass cases all on the same principle. The brass edges

have largely decorative function, the structural strengths comes from

glueing the glass panes together. McNarry uses clear silicone sealant,

which I also did until one Saturday afternoon I discovered that the

cartridge had set. I then tried in my desperation the general purpose

glue UHU® and literally

'stuck' to it. To date my glass cases have survived several moves

around Europe.

Glass is not exactly cheap and oblique

cuts and precise dimensions add

to the cost. In fact, the display case is the most expensive part of

the model, not counting the work on it. I have the glass cut in the

shop and go over the edges with emery paper, making sure that no grains

get onto the surface. The panes are carefully cleaned using first water

with washing-up liquid and then white spirit. The case is then

provisionally assembled using clear tape. making sure not to touch the

edges that need to be glued and ensuring proper alignment. One pane at

a time is taken off the assembly and stuck back on, the top being the

last piece. The glue takes some time to dry, so there is enough time to

correct the alignment.

I begin with the glass part of the case

because it so much easier to

cut

wood to exact dimensions than glass. The base is built to fit the glass

case. It usually consists of a piece of thick plywood or builders board

around which a frame like an inverted picture frame is constructed. I

love the combination of mahagony and brass and so dye and varnish the

wood to resemble this wood.

With the glass case in place on the base,

the 'frames' of L-shaped

brass profiles can be fitted. I begin with the socket around the case,

which is actually stuck to the wooden base rather than to the glass.

The rough mitres can be cut with a pair of nippers. Fine fitting is

done by grinding down the mitres on the PROXXON pillar drill fitted

with an abrasive stone and a mitre guide. Carefully done, the joints

become almost invisible. Before glueing on, the brass is de-oxidised

using fine steel wool and degreased by wiping it down with acetone. The

different pieces are provisionally attached using sellotape and the fit

adjusted step by step. Once I am satisfied with the fit, the pieces are

taken off one by one and

glued down.

Literature:

DREWS,

R.A. (1945): A Gilbert

Islands Canoe.- American Anthrop., New Ser., 47: 471-4.

FALCK,

W.E. (2002): Boote der

Gilbert-Inseln (Kiribati, Mikronesien).- LOGBUCH, 2/2002: 146-150.

GOETZFRIDT,

N.J. (1992):

Indigeneous

Navigation and Voyaging in the Pacific — A Reference Guide.-

Bibliographies and Indexes in Anthropology, No. 6, New York etc.

(Greenwood Press).

GREENHILL,

B. (1976): Archaeology

of the

Boat.- 319 pp., London (A. and C. Black).

GRIMBLE,

A. (1924): Canoes in the

Gilbert

Islands.- J. Royal Anthrop. Inst. ...: 54:

101-39.

IRWIN,

G. (1994): The Prehistoric

Exploration and

Colonisation of the Pacific.- 240 S., Cambridge (Cambridge University

Press).

IRWIN,

G. (1998): The Colonisation

of the Pacific

Plate: Chronological, Navigational and Social Issues.- J. Polynesian

Soc., 107(2): 111-43.

HADDON,

A.C., HORNELL,

J. (1936-38): Canoes

of Oceania.- 3 Vols., Bernice

P. Bishop Mus. Spec. Publ.,

27/28/29,

Honolulu, Hawaii (Reprint 1976).

KOCH,

G. (1965): Die materielle

Kultur der

Gilbert-Inseln.- Veröff. Mus. Völkerk. Berlin, Neue Folge 6,

Abt. Südsee III: 216 pp., Berlin (SMPK).

KOCH,

G. (1984): Boote aus

Polynesien und

Micronesien.- in: KOCH, G. [Hrsg.]: Boote aus aller Welt —

Katalog der Ausstellung 30.01.-05.05.1985, Berlin-Dahlem: 11-31,

Berlin (SMPK/Frölich & Kaufmann).

NEYRET,

J. (1976): Pirogues

Océaniennes,

Tome II — II. Polynésie, III. Micronésie, IV.

Indonésie,

V. Inde, VI. Autres Continents.- 315 pp., Paris (Assoc. des Amis

des Muséés

de la Marine).

Contact:

webmaster at wefalck dot eu